Máire was one of the most courageous people I have ever met. Did I already say that? Probably I did, because it’s what I think. When the doctors told her that there was not any further chance to recover, she asked them simply how long she could still have at her disposal and the answer was that it would have been a matter of few weeks. She informed me immediately, with controlled resignation, without any drama, sober and cleverly pragmatic, as she had always been. She told me she had still time to settle all the necessary matters for her family and then she hoped to slip peacefully away when her time would reach the end.

After that conversation, we kept on being in touch several times a day, as always, until she had strength enough to type at least a short message on the keyboard of her tablet or her mobile phone.

She remained always the same with me and we, believe it or not, kept on joking about little things as well.

Once she told me she was afraid, but she added that it was not a constant feeling, but just one which occasionally made surface among the others for a short time.

We have always spoken about all with each other and we did it until it was possible. But this is something very private.

Since her death I have thought of her every day. I speak to her in my mind and often I’m nearly surprised because she doesn’t answer, then I realize in reality she keeps on having a dialogue with me, based on all what we have exchanged during the years of our friendship. When you come to know a friend deeply, you can also imagine–with reasonable chance to be right–what your friend would have thought or said in a determined circumstance.

During these last months I have started re-reading a book which I consider very thought-provoking.

I like reading the books I like again and again. Every time I find a renewed enriching pleasure in that.

My criterion to determinate if a book is at my taste or not is asking myself if I feel like reading it again.

In this specific case it’s a book I can read several times.

It’s not a fiction book; it’s something between autobiography and philosophical essay, spiced with a good dose of British humour and a pinch of gentle irony.

Its title is “Nothing to Be Frightened of” by Julian Barnes.

I don’t feel comforted at all by absolute certainties which other might teach me. I need to find answers by myself, with my own speculations, which might be totally at random, I know. But like in travelling what is really worthy is not the final destination, but the trip we take to reach it, also in intellectual speculations I do think it’s more important the mental action of search rather than the sure answer one might find.

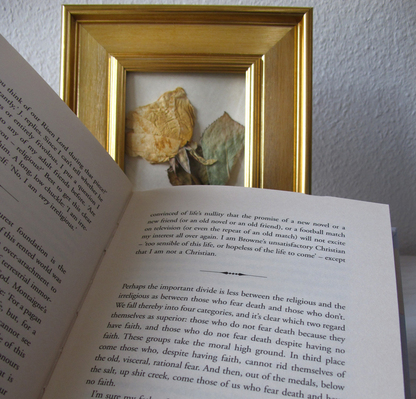

I took the average photos I’m posting here only a few hours ago, because they are in a way a source of inspiration to put a veneer of order in my confused thoughts.

I have never liked the habit to commemorate a dead by posting photos of flowers either withered or not, particularly if the flowers come from a personal stock of photos and have nothing to do directly with the person one is supposed to commemorate.

If by chance someone is reading these lines in this hidden corner of the virtual space, this person might reproach my lack of consistence, since on the background; here in these photos a withered rose is quite visible. But this is a flower with a meaning, not just a stereotyped symbol of death, used as decoration for a virtual card.

The one who gave me this withered rose knows what I mean.

So Máire left one year ago and she left me with all the spiritual questions which I cannot discuss with her anymore.

I don’t consider dull thinking over about death. It’s part of life, it’s part of us. Maybe it’s too oversimplified, but I’m inclined to think that when we die we go exactly where we were before being conceived, nowhere or maybe everywhere.

Máire once told me that occasionally she was afraid. I think we are afraid of what we don’t know, like children who are afraid of darkness, because they cannot see what there is around them and they can imagine that monsters can pop out from dark. Their mother, to reassure them, switches on the light and shows them that there is nothing unfamiliar in their room and even under the bed there are only their harmless slippers and nothing else.

The problem is that there is not and switch which can allow us to see clearly in certain mysteries of our ephemeral existence, but, on the other hands we are also supposed to be adults, which is a heavy responsibility, with positive sides.

Máire and I used to speak often of many topics like that, which we mixed merrily with much lighter subjects in a kind of messy, but lively exchange of thoughts.

Now I must keep on doing that without her.

A polished stone she picked up one day in one of her walks along the sea. She thought I might like it and of course she was right. A shining polished stone, as green as her Ireland. It’s her on my desk. A concrete fragment of our never-ending friendship.

Tá sé deas a bheith do chara, Máire!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed